RAID is unlike any other drill. It’s designed to drill deeply and quickly through glacial ice in order to penetrate the oldest ice at the bottom and then drill ahead into bedrock below. Because of the great depths, low temperatures, different media (ice to rock), environmental protection, and difficult operating conditions, it was custom designed inside and out. In order to meet these challenges, the RAID drill integrates innumerable components in a complex system. For example, the seemingly simple process of separating ice cuttings from drilling fluid involves a connected network of fluid tanks, pumps, valves, temperature sensors, flow meters, fluid level sensors, heaters, chillers, filters and mechanical separators — all controlled by an industrial-type automation interface. The advantage of this is that the drill can be operated by only a few people. The disadvantage, however, is that there are many potential points of failure. More on this in a bit.

No matter how carefully and systematically we designed the equipment back home, we rely on a field team of skilled engineers, drillers, and technicians to make it all work. In the field, it all comes down to people. This year we have a hand-picked team to push development of the system forward.

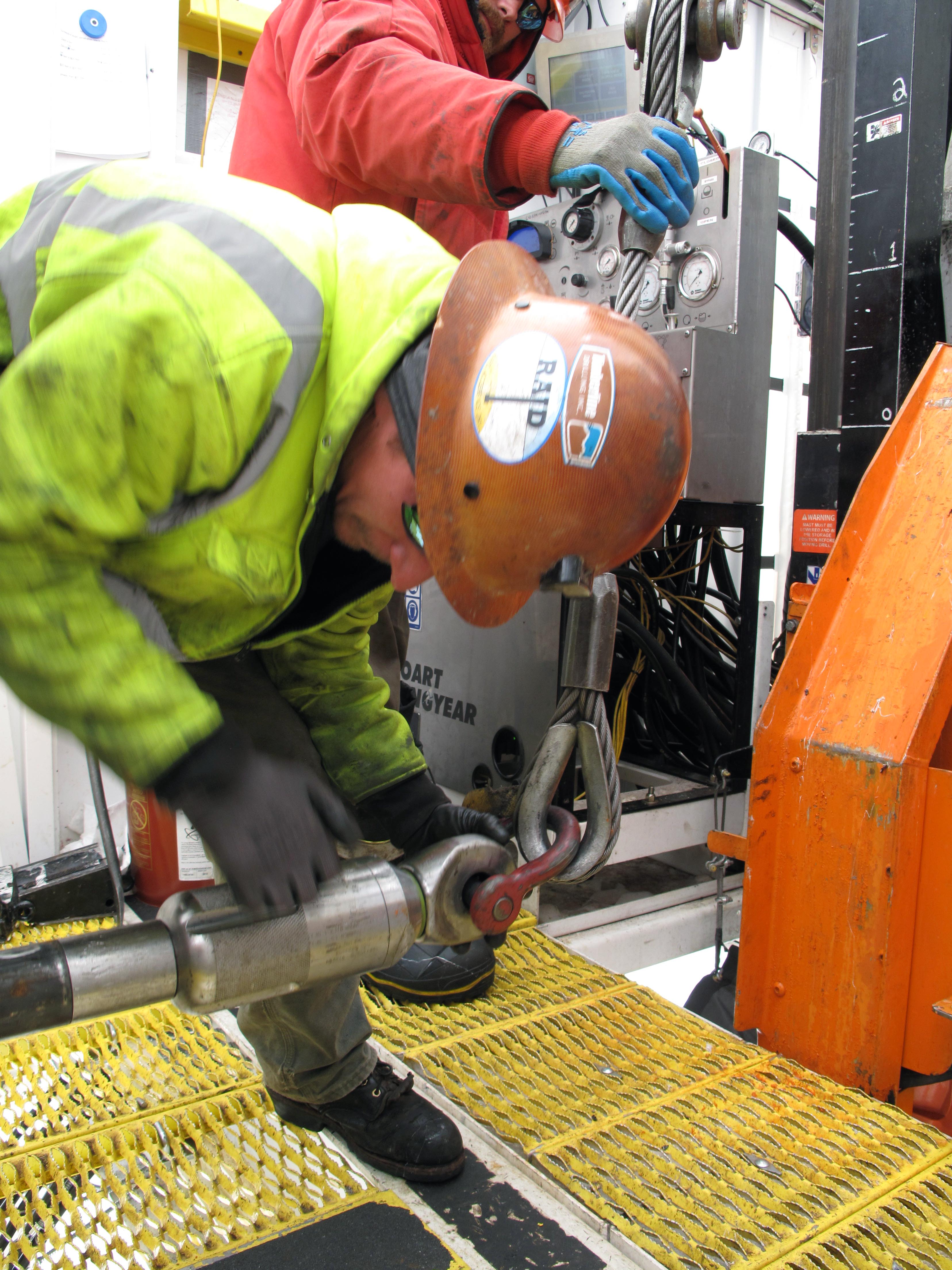

The drill itself is an industry standard rotary diamond drill made by Boart Longyear. It’s quite a bit bigger, more powerful, and different in concept that ice-coring drills commonly used in Antarctica to recover continuous ice cores. For this reason, we need drillers who are expert in operating large rotary drills. Four of our field crew are from Timberline Drilling, based in Idaho. In addition to their expertise as rock drillers, they also cover a wide gamut of skills as mechanics, including working with hydraulics, welding, electronics, and metal fabrication. As is required for drilling in any remote location — whether in Alaska or Antarctica — they are prepared to modify and repair just about any piece of equipment in the system. And RAID has definitely put them to the test.

Chris, Dave, Ray and Thor all bring different backgrounds and experience to this job, but one thing they all share is a dedication to getting the job done and taking professional pride in doing things right. They are eager to learn, revel in the challenges, and are humble in the face of new situations.

Oh, and I should add that they can all pull a wrench like nobody’s business.

Although this Timberline group is new to working in Antarctica and new to the bespoke RAID drilling platform, they have taken ownership of it as if they were there from the beginning. Sometimes I’m sure it seems to them that they have inherited a beast — a fickle, temperamental and quirky tangle of equipment allegedly meant to drill ice and rock. But I also think they have come to recognize that drilling into firn, ice, mud and rock requires a unique approach that this drill is meant to handle.

Along with these drillers, we have added several other key people, all with special skills and prior Antarctic and Greenland field experience. These include Jay, an expert engineer and ice driller, Shawntel, a field technician with deep experience in ice coring operations, and Owen, a hydraulic engineer who is adept at working on just about any mechanical system he faces. Don and AJ round out the team as engine mechanic and fluid circulation specialist, respectively.

Operating our system in the field while continuing to develop and perfect it requires ingenuity. A great example arose with failure of a pressure relief valve that we installed just last season in order to regulate drilling fluid pressure so that we don’t fracture the ice (hydrofracking). We quickly discovered that the new valve was susceptible to clogging up, rendering it useless. Unfortunately, there is no Home Depot nearby. So we found an older, simpler type of valve in our shop, but it is rated to activate at about 1100 psi of pressure. That is way too high — we need to set this valve to about 70 psi to prevent ice fracking, requiring a spring with much less stiffness. After a long scavenger hunt through the shop, the team took apart the old valve unit, found a spring of about the right size in another device, fabricated a brass cylinder that could hold the spring in place, and adjusted the spring until it gave the right pressure activation point. It works!

This season we’ve discovered all kinds of problems that had never appeared before. It seems like problem-solving Whack-a-Mole. You fix one thing and then something else that has never failed before decides to take a day off. So far, we’ve been able to deal with the myriad issues one by one, but it takes time, patience, and creativity. It would be easy to be defeated by any one of them, but this team responds by isolating the problems and working up solutions, often using tools, materials and devices not intended for that purpose.

As we continue to overcome problems, we are making slow progress with drilling. We’re taking it one foot at a time drilling in ice, making adjustments in every part of the system in order to find the sweet spot of penetration and chip transport. As we go deeper, it should become easier with the colder temperatures, reducing the tendency for ice chips to pack together and clog the fluid lines. But for now, we’re cutting ice at our fastest rate yet and may soon set a new RAID depth record! Hooray for small successes!

Photos by John Goodge.

The views expressed here are personal reflections that do not represent either the RAID project or the National Science Foundation.